$19.99 plus $5.01 S&H

Price: $ 25.00 (USD)

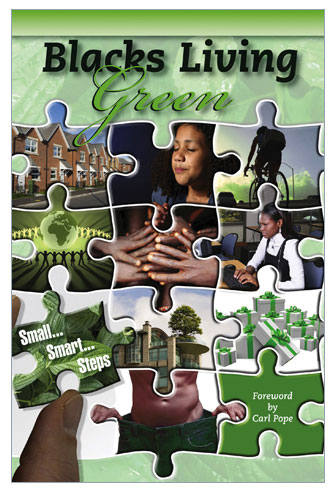

Blacks Living Green

By Dr. Sharon T. Freeman

(Paperback)

AASBEA, January 2009

ISBN 978-0-9816885-1-0

Foreword by Carl Pope

Dear Readers:

Why this book, and why now?

After all, aren’t we are on the verge of watching America’s first African-American President go greener than any of his predecessors, judging from his promises—and more important—from his performance to date?

Well, unless I missed my guess we will shortly begin to see articles asking quizzically, “how come?” How did a community organizer on Chicago’s South Side come out of his experience so focused on sustainability? Why is he so committed to action on clean energy and global warming?

After all, environmental engagement is not part of the media frame about the African-American community (or that of the Hispanic-American or Asian-American community for that matter).

It doesn’t matter that the most solidly environmental block in the Congress has been, for twenty years, the Black Caucus.

Jesse Jackson, Sr.’s powerful environmental platform has been simply forgotten. It doesn’t matter that African American Mayors like Los Angeles’s Tom Bradley, or County officials like King County, Washington’s Ron Simms, have been providing environmental leadership for decades.

Nor can the media actually absorb polling results that have shown for years that the African American population is more concerned about pollution than the Euro-American community – understandably, since they suffer from more of it. Similarly, African Americans are more excited about solar power, more skeptical of corporate greenscamming, and more convinced that good jobs are clean jobs than anyone else in America.

Every time these results appear and are pointed to, reporters are stunned. They call me. “Why is this happening? What is the source of this huge change? Are these numbers real?” And when I tell them that this happened long ago, that this is not a change but an expression of a long-standing community concern, and that, yes, the numbers are real, that’s when they lose interest. Something that has been true for a long time, but that we don’t understand, doesn’t fit as “news.”

We can’t rely on the media aren’t to inform us.

To paraphrase Ralph Ellison, African Americans are our “Invisible Environmentalists.” And as Ellison pointed out, poignantly, invisibility matters. Invisibility hurts. Invisibility divides.

One of the obstacles that President Obama had to overcome on his pathway to the White House, the media kept reminding us, was that Obama was “different.” (He made a fair number of jokes about that himself – gentle jokes, to show that he got it.) Many Americans weren’t comfortable with him. And it’s very clear that it was not so much the man himself who was different – it was the color of his skin, and the perceived nature of his community. He was assumed to have different experiences, different attitudes, and different priorities – and his environmental beliefs were a part of that perceived difference.

What Sharon Freeman has done with “Blacks Living Green” is to try another approach to make visible the invisible, to make familiar the unfamiliar, to show that Barack Obama’s concerns and values about the environment come out of his experience with his community – because his community is seamlessly engaged in the American struggle, and effort, to make the way we live compatible with the future we imagine for our children.

She does this in the only way that can really change the frame – she tells the story of ordinary people, doing ordinary things, in an intentioned and conscious way – more sustainably. And this is not always easy – the fact that our society doesn’t make sustainability easy is just as true for African Americans as it is for anyone else – and that common struggle is one of the connections that Sharon makes tangible in this book.

And this book does something else. Because the rest of us don’t usually think about living green as a part of the Black experience, she gives us a fresh look at issues and struggles that we face, but that we may have simply become accustomed to.

What does happen when an automobile parts supplier loses his business after 9-11? Learning how Frederick Carter, so firmly planted “in the carbon world” as he put it, reached back to his upbringing in rural Mississippi and founded a Permaculture Institute near Chicago is a fresh view of the sustainability journey that has been told so often, for Americans whose formative experience was NOT watching the body of a cousin who had been lynched, Emmett Till, floating down a river.

Kathryn Underwood’s pathway to a passionate urban planner also begins in her youth, but in her case that youth is in urban Detroit, and she reminds us that for urban blacks, the strongest connection to the land was often one also driven by economic reality – gardening.

And Washington, DC Mayor Adrian Fenty puts a new face on the need for leaders to model sustainable behavior – given our historic social stereotypes about African Americans and motor vehicles, having Mayor Fenty switch to a “Smart Car” helps counteract the usual argument that green vehicles are only for Hollywood types.

One of the core lessons of the last thirty years is that just as we all live under one sky, and ultimately share one climate, and one biosphere, we all share one environmental destiny. Our failure to clean up toxic incinerators in our inner cities has polluted our fisheries far from those neighborhoods. The reckless practices of oil refineries next to African American communities in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley were simply the most tangible proof that wherever they found weakness, oil companies would cut corners – and they didn’t stop cutting corners when they got to the pristine areas of Alaska’s North Slope.

So the stories in this book are important – they embody hope, they embody struggle, and they embody connectedness – as an environmentalist, I’m glad to be in this together.

And if we reflect on the stories in this book, we’ll probably have a better grasp of the man we just elected to get this country out of the biggest mess in seventy years.

Be inspired,

Carl Pope

Executive Director

Sierra Club